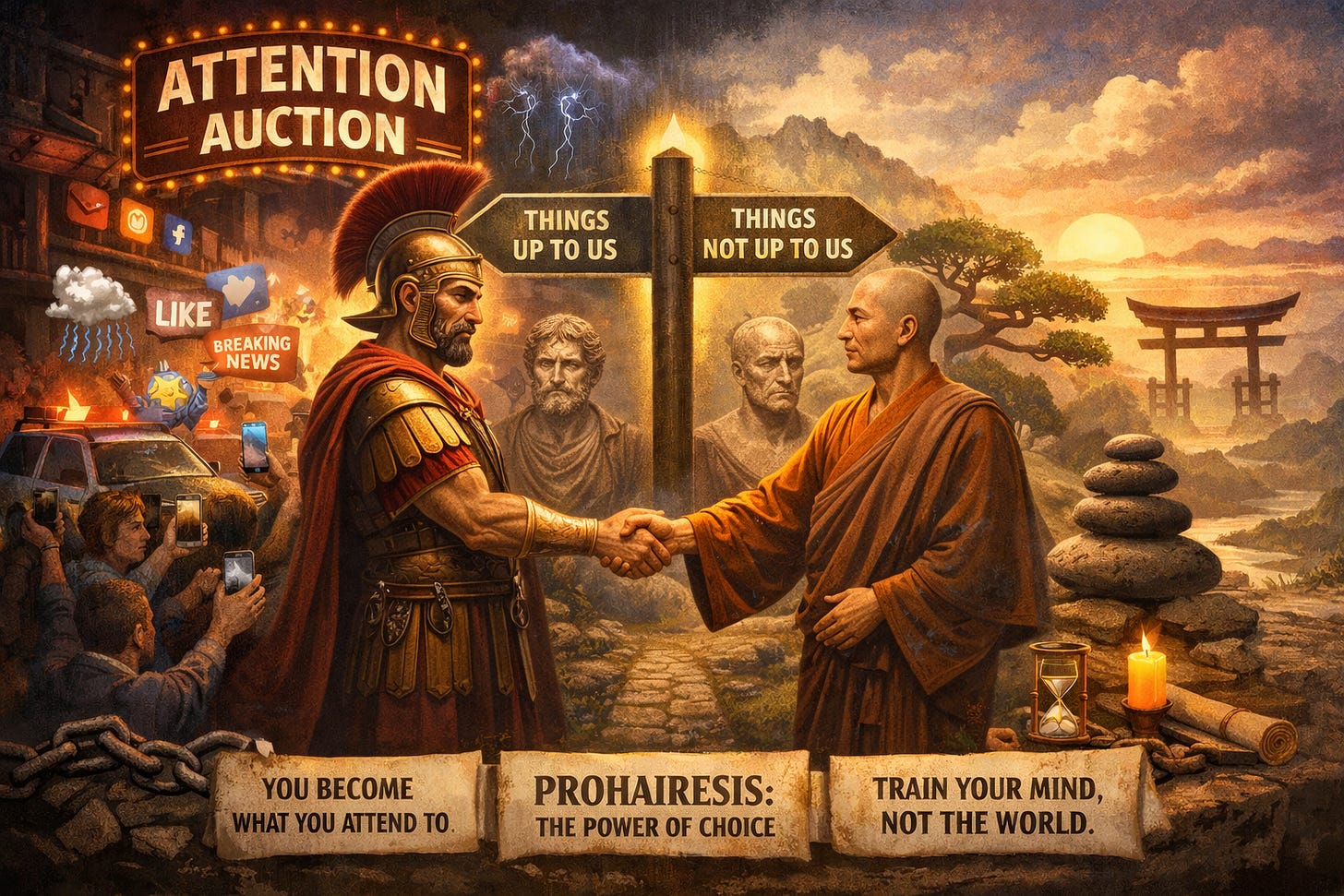

The Attention Auction

Stoicism and Zen

We don’t get to opt out of the auction.

The world is always bidding. Sirens wailing their little emergencies, algorithms slipping dopamine postcards into the slot machine of your thumb, even the weather doing its passive-aggressive thing with sudden rain or that one perfect blue-sky day that makes guilt feel mandatory if you’re indoors.

It’s almost comical how we’ve engineered an environment that treats attention like it’s public property. Social media doesn’t just want your eyes; it wants the next thirty seconds of your life, then the next, until you’ve paid rent on a mental real estate you never signed for. And the more fragmented the bids become, the less any of us owns the deed to our own minds.

Yet here’s the twist: agency isn’t gone. It’s just expensive. Choosing where to aim the spotlight costs friction. It means turning notifications into exiles, walking past the siren song without humming along, deciding that the news can wait while you finish the sentence that’s actually yours. Most days it feels less like empowerment and more like low-key rebellion against a machine designed to make attachment feel effortless.

Epictetus

Epictetus had it right centuries before the feed existed: we become what we attend to. Not metaphorically. Mechanically. Pour your gaze into outrage? You grow thorns. Feed it to a single quiet task? Something solid starts to form, maybe even something resembling a self that isn’t just reactive static.

Yeah, the environment is loud, relentless, engineered for capture. But it still has to ask permission at the door of your skull. The refusal doesn’t have to be dramatic, just consistent, boringly stubborn, like a poet who keeps writing the same line until the world gets tired of interrupting.

Epictetus stated it like physics. Attention is the forge, and you’re the metal. Heat it with outrage loops and the blade comes out serrated, brittle, always looking for the next fight. Hammer it patiently against one deliberate thing—wood under a chisel, code that finally runs clean, a sentence that survives three rewrites—and something denser emerges. Not flashy. Just less porous to every passing distraction.

There’s a quiet species of solidity that only forms under sustained, voluntary gaze. Read a hard book slowly enough that you forget you’re “reading for content” and start noticing how the sentences breathe. Sit with one instrument until the wrong notes stop feeling like failure and become melody. Walk the same block at dawn until the light changes stop being background and become architecture. Incremental density. The self stops being a weather vane and starts being a stone foundation.

It costs nothing yet everything. No subscription fee, no guru required. Just the boring heroism of saying no to the siren one more time than feels reasonable. Most mornings, I suspect half the battle is simply remembering that the choice still exists, even when the feed is screaming otherwise.

The Enchiridion

Literally “the little thing you keep in your hand,” like a pocket knife or a cheat sheet for not losing your mind—sits there in its fifty-three short, brutal sections, pretending to be modest while quietly dismantling most of what passes for human misery. Compiled by Arrian from Epictetus’s lectures around 135 CE, it’s the Stoic equivalent of a field manual: no fluff, no metaphysics for metaphysics’ sake, just instructions for how not to be a slave to everything that isn’t you.

Some things are up to us (prohairesis—our judgments, impulses, desires, aversions, basically the machinery of assent inside the skull); everything else is not (body, property, reputation, offices, the weather, other people’s opinions).

The first category is free by nature; the second is weak, slavish, obstructed. Epictetus doesn’t soften it. If you chase or fear what’s external, you’re volunteering for chains you were born without. He turns philosophy into a physics of the self. Pour attention into what you can’t control? You forge anxiety, resentment, a life that’s mostly flinch. Direct it inward, to how you interpret events? Something less porous starts to form.

Don’t demand that things happen as you wish; wish them to happen as they do, and you’ll flow with reality instead of drowning in it.

You’re a brother, mother, citizen, daughter, son—play the parts well, but remember the actor isn’t the costume.

When death comes, it won’t ask your opinion. Practice seeing it indifferently now, so the event itself loses its sting.

The daily audit - morning preview what might go sideways; evening review where you assented badly. No drama, just bookkeeping.

Prohairesis is the quiet, unflashy core of Epictetus’ whole machine. It’s the faculty that decides whether to assent to an impression or kick it to the curb. The rational, governing choice. The moment your mind says “yes, this is how things are” or “no, that’s bullshit” to whatever the world throws at your perception. It’s the hinge between freedom and slavery. Animals react, plants grow. we? Humans judge the impression first. That judgment is prohairesis at work.

Epictetus opens the Discourses with the famous fork: some things are up to us, some aren’t. The “up to us” bucket contains exactly one resident: prohairesis. Your body? Not yours to command forever. Reputation, money, the weather, the time? All leased from the cosmos.

But how you interpret the siren, the tweet, the slight, the diagnosis? That’s yours. Call the indifferent good or bad, and you hand the keys to externals. See them as indifferent, judge only your response, and you’re free even in chains.

The good life, for Epictetus, isn’t virtue in the abstract; it’s prohairesis “in accordance with nature”—a steady, unimpeded state where you want what happens, because you’ve trained the faculty to see events as raw material, not as moral verdicts. Externals are indifferent; the use you make of them via prohairesis is everything. Good prohairesis = virtue in motion. Bad = vice, thorns, reactive static.

Marcus Aurelius

Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius orbit the same Stoic sun, but from different altitudes. Epictetus, the former slave turned sharp-tongued teacher, hammers out the Enchiridion like a pocket survival kit: terse, ruthless, almost surgical.

Marcus, the emperor scribbling in camp tents amid plague and frontier wars, turns the same doctrines into a private diary of reminders—gentler, more melancholic, laced with cosmic weariness. Both insist the auction for your attention is rigged against you, yet the tone, structure, and flavor diverge in ways that feel almost biographical.

The Enchiridion opens with the famous fork (”some things are up to us, others are not”) and never lets go. Everything funnels there: train desire to want only what’s inevitable, action to suit your roles without attachment, assent to see impressions for what they are.

Marcus absorbs all that. He quotes Epictetus directly in places, leans hard on the dichotomy, but refracts it through the lens of someone who can’t escape the externals. The Meditations aren’t for teaching others; they’re self-administered medicine.

Marcus speaks of the ruling principle, or simply “the mind” that judges harm, but the function is identical: the power to decide whether an event wounds you. “The mind determines what makes what happens harmful.” Events are neutral; your interpretation colors them.

Yet where Epictetus might snap “that’s not up to you, drop it,” Marcus lingers: he thanks people for lessons, pities the ignorant, urges compassion toward the flawed because they’re kin in the rational cosmos.

The emperor’s prohairesis operates under heavier gravity—family deaths, betrayals, the endless grind of ruling—yet he keeps reminding himself to align it with nature: act justly, speak truth, accept the flux.

Epictetus is the street-fighter Stoic: quick jabs, no mercy for self-pity. Marcus is the weary monarch trying to stay upright in armor that’s too heavy: more poetic, more haunted by time’s theft (”Soon you’ll be ashes or bones”), more tender toward humanity’s shared fumbling.

Epictetus says detach from roles (”play the part well, but remember you’re the actor”); Marcus plays emperor with quiet grandeur, weaving social duty into the fabric (”whatever anyone does or says, I must be a good man”).

In the end, Marcus reads like a man who studied Epictetus so deeply he internalized the manual, then had to live it at scale. Less theory, more quiet heroism against entropy. The Enchiridion equips you to survive the world. The Meditations show what ruling it feels like.

Seneca

Seneca’s Letters to Lucilius slide into the Stoic conversation like a well-bred Roman correspondent who’s seen too many banquets and too much blood.

Where Enchiridion is a pocket-sized scalpel, Seneca’s letters unfold like a long, elegant dinner conversation that keeps circling back to the same uncomfortable truths: time slips away, death waits politely, virtue is the only thing worth owning, and everything else is rented furniture. Both men are drilling the same core mechanics: externals are indifferent; suffering comes from bad judgments; train the mind to assent only to what’s rational and virtuous.

Seneca, the millionaire statesman who advised Nero, conducts a civilized correspondence over wine, meandering, eloquent, full of anecdotes and literary flourishes. He admits his own faults openly. The letters feel personal, therapeutic, almost novelistic. Seneca converses in elegant prose while the world burns.

Stoicism and Zen

Stoicism and Zen sit across an ocean and a millennium from each other, yet they keep bumping elbows. Both are low-drama survival kits for a mind that’s constantly getting mugged by reality. Both say the auction for your attention is rigged, both hand you the latchkey to your own skull.

Oddly, maybe inevitably, they arrive at almost the same place via almost opposite roads—one armed with logic like a Roman engineer, the other with a finger pointing at the moon while insisting the finger isn’t pointing at the moon.

Similarities first:

Control what you can, drop the rest. Epictetus’ dichotomy of control maps to Zen’s refusal to cling. Events, people, the body decaying, the empire crumbling—none of it is “yours” in any ultimate sense. Stoics call externals indifferent; Zen calls them empty of inherent self . Both train you to stop fighting the current and start floating in it without drowning.

Present-moment density. Marcus Aurelius looping “right now, this moment” like a mantra; the Zen admonition to chop wood, carry water, eat when hungry, sleep when tired. No rumination on yesterday’s slight or tomorrow’s invoice. The auction quiets when you stop bidding on ghosts.

Desire as the thief. Stoics tame passions by re-judging impressions. Zen sees craving as the itch that makes everything scratchy. Both aim for a mind that doesn’t flinch at pleasure or pain because it’s not owned by either.

Simplicity as armor. The ethos is minimal: virtue over stuff, awareness over accumulation. Zen’s teahouse aesthetic mirrors Epictetus—refuse to let externals rent space in the head.

Practice over theory. Stoic exercises (premeditatio malorum, journaling, role-playing roles without role-trapping); Zen’s zazen, koans, samu (mindful work). Both are do-it-yourself forge work: sit, observe, correct the grasping until the static thins.

The Divergences:

Razor logic vs. deliberate nonsense. Stoicism is propositional, forensic. Zen is designed to short-circuit the rational mind until it gives up and sees directly. Stoics trust reason to map the logos; Zen masters laugh at reason when it pretends to own the territory. One builds a fortress of clear judgments; the other demolishes the builder.

Goal framing: virtue/endurance vs. radical awakening. Stoics pursue eudaimonia through the four virtues (wisdom, courage, justice, temperance)—a steady, rational alignment with nature. Zen aims at satori/enlightenment: sudden glimpse that there’s no separate self to defend, no suffering once the illusion drops. Stoicism dulls suffering by accepting it; Zen seeks to eradicate its root by seeing through the self that suffers.

Tone and texture. Stoics can feel austere, duty-bound, a bit grimly heroic. Zen has a mischievous edge, a gale of laughter when the bottom falls out. Stoicism is the weary emperor reminding himself to stay kind. Zen is the amused old monk pouring tea while the house burns.

Metaphysics lite vs. metaphysics dissolved. Stoics nod to a providential cosmos, a rational logos threading everything. Zen say no ultimate self, no ultimate other. Stoics play chess with concepts. Zen kicks over the board.

Stoicism equips you to see the storm with clear eyes.

Zen says notice that the storm isn’t separate from the eyes noticing it.

One feels like rebellion. One feels amused surrender.

Both work. Dealer’s choice.

Sharp parallell between the Stoic dichotomy and Zen's non-clinging. I dunno if most people realize that the attention metaphor actually predates social media by centuries - Seneca was basically complaining about the same thing with Roman social obligations. I tried applying the premeditatio malorum exercise for a week and it felt wierd at first, but it did shift something about how mornings landed. The auction never stops, but the bidding does get quieter.

I was exposed to Stoicism since young and incorporated many of its tenets in my life. But the longer I live, the more I think this philosophy is most relevant now than ever before. I am glad to see its resurgence because the young generations need all the help they can get to not be swallowed by the void of the shallow and inconsequential….

Great post!